| |

Murad IV 1612-1640 1623-1640 |

Murad IV (W)

Murad IV 1612-1640 1623-1640 (W)

Family

- Family (W)

Consorts

Very little is known about the concubines of Murad IV, principally because he did not leave sons who survived his death to reach the throne, but many historians consider Ayşe Sultan as his only consort until the very end of Murad's seventeen-year reign, when a second Haseki appeared in the records. It is possible that Murad had only a single concubine until the advent of the second, or that he had a number of concubines but singled out only two as Haseki. Another consort of his may have been Sanavber Hatun, though certainly not of the Haseki rank, whose name can be found on the deed of a charitable foundation as "Sanavber bint Abdülmennan".

- Sons

- Şehzade Ahmed (21 December 1628 – 1639, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Blue Mosque, Istanbul)

- Şehzade Numan (1628 – 1629, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Blue Mosque, Istanbul)

- Şehzade Orhan (1629 – 1629, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Blue Mosque, Istanbul)

- Şehzade Hasan (March 1631 – 1632, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Blue Mosque, Istanbul)

- Şehzade Suleiman (2 February 1632 – 1635, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Blue Mosque, Istanbul)

- Şehzade Mehmed (11 August 1633 – 11 January 1640, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Blue Mosque, Istanbul)

- Şehzade Osman (9 February 1634 – 1635, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Blue Mosque, Istanbul)

- Şehzade Alaeddin (26 August 1635 – 1637, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Blue Mosque, Istanbul)

- Şehzade Selim (1637 – 1640, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Blue Mosque, Istanbul)

- Şehzade Mahmud (15 May 1638 – 1638, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Blue Mosque, Istanbul)

Daughters

Murad had three daughters:

- Kaya Sultan alias Ismihan (1633-1659, buried in Mustafa I Mausoleum, Hagia Sophia Mosque, Istanbul), married August 1644, Melek Ahmed Pasha;

- Safiye Sultan (buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Blue Mosque, Istanbul), married 1659, Sarı Hasan Pasha;

- Rukiye Sultan (died 1696, buried in Ahmed I Mausoleum, Blue Mosque, Istanbul), married firstly 1663, Şeytan Divrikli Ibrahim Pasha, Vizier, married secondly 1693 Gürcü Mehmed Pasha.

|

|

|

|

|

Murad IV (Ottoman Turkish: مراد رابع, Murād-ı Rābiʿ; 27 July 1612 – 8 February 1640) was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1623 to 1640, known both for restoring the authority of the state and for the brutality of his methods. Murad IV was born in Constantinople, the son of Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603-17) and Kösem Sultan. He was brought to power by a palace conspiracy in 1623, and he succeeded his uncle Mustafa I (r. 1617-18, 1622-23). He was only 11 when he ascended the throne. His reign is most notable for the Ottoman-Safavid War (1623-39), of which the outcome would permanently part the Caucasus between the two Imperial powers for around two centuries, while it also roughly laid the foundation for the current Turkey–Iran–Iraq borders.

|

| |

Early life

Early life (W)

Murad IV was born on 27 July 1612 to Ahmed I (reign 1603-1617) and his consort and later wife Kösem Sultan. After his father’s death when he was six years he was confined in the Kafes with his brothers, Suleiman, Kasim, Bayezid and Ibrahim.

Grand Vizier Kemankeş Ali Pasha and Şeyhülislam Yahya Efendi were deposed from their position. They did not stop their words the next day the sultan, the child of the age of 6, was taken to the Eyüp Sultan Mausoleum. The swords of Muhammad and Yavuz Sultan Selim were besieged to him. Five days later he was circumcised.

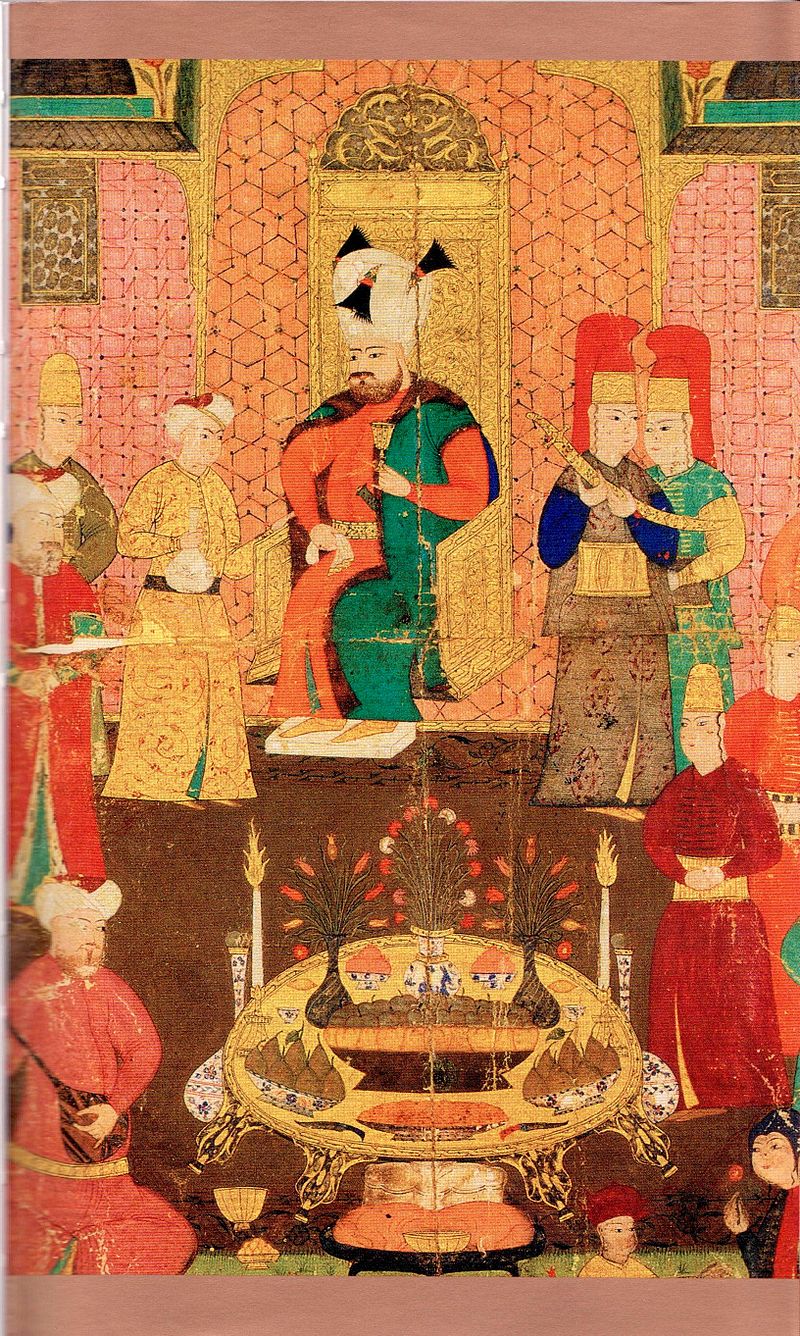

Ottoman miniature painting depicting Murad IV during dinner. |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Reign

|

Early reign (1623-32)

Early reign (1623-32) (W)

Murad IV was for a long time under the control of his relatives and during his early years as Sultan, his mother, Kösem Sultan, essentially ruled through him. The Empire fell into anarchy; the Safavid Empire invaded Iraq almost immediately, Northern Anatolia erupted in revolts, and in 1631 the Janissaries stormed the palace and killed the Grand Vizier, among others. Murad IV feared suffering the fate of his elder brother, Osman II (1618-22), and decided to assert his power.

At the age of 16 in 1628, he had his brother-in-law (his sister Fatma Sultan's husband, who was also the former governor of Egypt), Kara Mustafa Pasha, executed for a claimed action "against the law of God".

After the death of the Grand Vizier Çerkes Mehmed Pasha in the winter of Tokat, Diyarbekir Beylerbeyi Hafez Ahmed Pasha became a vizier and an emperor on 8 February 1625.

The epidemic, which started in the summer of 1625 and called the plague of Bayrampaşa, spread to a threat to the population of Istanbul. On average, a thousand people died every day. The people went to the Okmeydanı, to regent themselves from this plague. The situation was worse in the countryside, but there is no one who sees what looks out of Istanbul. |

|

|

|

|

Absolute rule and imperial policies

Absolute rule and imperial policies (1632-1640) (W)

Murad IV tried to quell the corruption that had grown during the reigns of previous Sultans, and that had not been checked while his mother was ruling through proxy.

Executions were issued to the states, and those who came to Istanbul under the pretext of Jelals and executed were ordered. Murad IV shivering and brutal sultan started with this shaking.

Ilyas Pasha, who took advantage of the confusion in Istanbul and dominated the Manisa and Balikesir sides, who was taught Şehname, Timurname at night and was caught in the sultan's dreams, was finally caught and brought to Istanbul and executed in front of the Sultan.

Murad IV banned alcohol, tobacco, and coffee in Constantinople. He ordered execution for breaking this ban. He would reportedly patrol the streets and the lowest taverns of Constantinople in civilian clothes at night, policing the enforcement of his command by casting off his disguise on the spot and beheading the offender with his own hands. Rivaling the exploits of Selim the Grim, he would sit in a kiosk by the water near his Seraglio Palace and shoot arrows at any passerby or boatman who rowed too close to his imperial compound, seemingly for sport. He restored the judicial regulations by very strict punishments, including execution, he once strangled a grand vizier for the reason that the official had beaten his mother-in-law. |

|

|

|

|

Fire of 1633

Fire of 1633 (W)

On 2 September 1633, the big Cibali fire broke out, burning a fifth of the city. The fire that started during that day when a caulker burned the shrub and the ship caulked into the walls. The fire, which spread from three branches to the city. One arm lowered towards the sea. He returned from Zeyrek and walked to Atpazan. Other kollan Büyükkaraman, Küçükkaraman, Sultanmehmet (Fatih), Saraçhane, Sangürz (Sangüzel) districts have been ruined. The sultan could not do anything other than watching sentence viziers, Bostancı and Yeniçeri. The most beautiful districts of Istanbul have been ruined, from the Yeniodas, Mollagürani districts, Fener gate to Sultanselim, Mesihpaşa, Bali Pasha and Lutfi Pasha mosques, Şahı buhan Palace, Unkapam to Atpazarı, Bostanzade houses, Sofular Bazaar. The fire that lasted for 30 hours could be extinguished after the wind sectioned. {!} |

|

|

|

War against Safavid Iran

War against Safavid Iran (W)

War against Safavid Iran

Murad IV's reign is most notable for the Ottoman-Safavid War (1623-39) against Persia (today Iran) in which Ottoman forces managed to conquer Azerbaijan, occupying Tabriz, Hamadan, and capturing Baghdad in 1638. The Treaty of Zuhab that followed the war generally reconfirmed the borders as agreed by the Peace of Amasya, with Eastern Armenia, Eastern Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Dagestan staying Persian, while Western Armenia, and Western Georgia stayed Ottoman. Mesopotamia was irrevocably lost for the Persians. The borders fixed as a result of the war, are more or less the same as the present border line between Turkey, Iraq and Iran.

During the siege of Baghdad in 1638, the city held out for forty days but was compelled to surrender.

Murad IV himself commanded the Ottoman army in the last years of the war. |

|

|

|

Relations with the Mughal Empire

Relations with the Mughal Empire (W)

While he was encamped in Baghdad, Murad IV is known to have met ambassadors of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, Mir Zarif and Mir Baraka, who presented 1000 pieces of finely embroidered cloth and even armor. Murad IV gave them the finest weapons, saddles and Kaftans and ordered his forces to accompany the Mughals to the port of Basra, where they set sail to Thatta and finally Surat. |

|

|

|

| |

Architecture

|

Architecture

Architecture (W)

Murad IV put emphasis on architecture and in his period many monuments were erected. The Baghdad Kiosk, built in 1635, and the Revan Kiosk, built in 1638 in Yerevan, were both built in the local styles. Some of the others include the Kavak Sarayı pavilion; the Meydanı Mosque; the Bayram Pasha Dervish Lodge, Tomb, Fountain, and Primary School; and the Şerafettin Mosque in Konya. |

|

|

|

| |

Music and poetry

|

Music and poetry

Music and poetry (W)

Murad IV wrote many poems. He used "Muradi" penname for his poems. He also liked testing people with riddles. Once he wrote a poemic riddle and announced that whoever came with the correct answer would get a generous reward. Cihadi Bey who was also a poet from Enderun School gave the correct answer and he was promoted.

Murad IV was also a composer. He has a composition called "Uzzal Peshrev". |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Murad IV (B)

Murad IV (1612-1640) (1623-1640) (B)

.jpg)

Oil on canvas, depicting the favourite consort of Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603-1617), known as Kösem or Mahpeyker Sultan, breastfeeding her son the future Sultan Murad IV (r.1623-1640) or Sultan Ibrahim (r.1640-1648), both figures wear extensive hardstone studded jewellery and large rounded cloth turbans, Kösem Sultan also wears golden brocade garments, fine white lace and jewel-studded pointed shoes, above the pair hangs a European-style red velvet curtain, in thin wood frame. (L) |

|

|

| |

|

Murad IV, in full Murad Oglu Ahmed I, (born July 27, 1612, Constantinople, Ottoman Empire [now Istanbul, Turkey] — died February 8, 1640, Constantinople), Ottoman sultan from 1623 to 1640 whose heavy-handed rule put an end to prevailing lawlessness and rebelliousness and who is renowned as the conqueror of Baghdad.

Murad, who came to the throne at age 11, ruled for several years through the regency of his mother, Kösem, and a series of grand viziers. Effective rule, however, remained in the hands of the turbulent spahis (from Turkish sipahiyan, quasi-feudal cavalries) and the Janissaries, who more than once forced the execution of high officials. Corruption of government officials and rebellion in the Asiatic provinces, coupled with an empty treasury, perpetuated the discontent against the central government.

Embittered by the excesses of the troops, Murad was determined to restore order both in Constantinople and in the provinces. In 1632 the spahis had invaded the palace and demanded (and got) the heads of the grand vizier and 16 other high officials. Soon thereafter Murad gained full control and acted swiftly and ruthlessly. He suppressed the mutineers with a bloody ferocity. He banned the use of tobacco and closed the coffeehouses and the wineshops (no doubt as nests of sedition); violators or mere suspects were executed.

In his foreign policy Murad took personal command in the continuing war against Iran and set out to win back territories lost to Iran earlier in his reign. Baghdad was reconquered in 1638 after a siege that ended in a massacre of garrison and citizens alike. In the following year peace was concluded.

A man of courage, determination, and violent temperament, Murad did not follow closely the precepts of the Sharīʿah (Islamic law) and was the first Ottoman sultan to execute a shaykh al-islām (the highest Muslim dignitary in the empire). He was able to restore order, however, and to straighten out state finances. Murad’s untimely death was caused by his addiction to alcohol. |

|

|

|

|

|

|